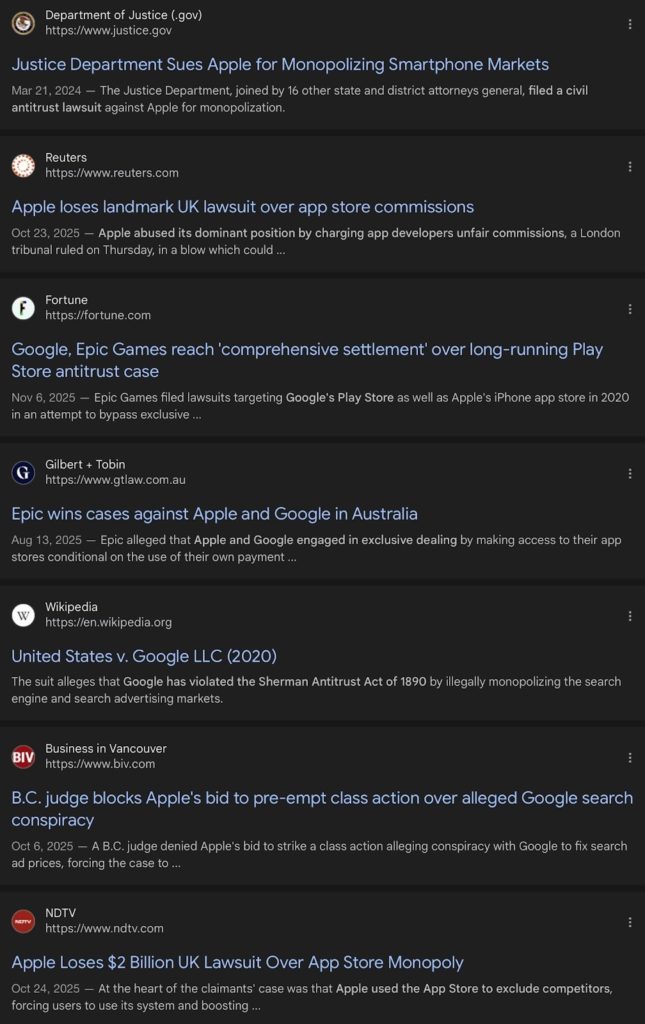

Both Apple and Google have spent a lot of time in courtrooms in recent years, defending themselves against charges of anticompetitive behavior surrounding their operating systems.

Their adversaries have claimed, with some success, that these two tech giants funnel all purchases between users and software developers through app stores that they control and tax. Depending on how recent rulings and agreements are enforced across various jurisdictions, shopping for apps could start to feel very different in the near future, as alternate app stores prepare to compete with the incumbents.

Although litigation continues, technological progress may soon present a practical solution to these legal battles. Apps have long been the gateways of the digital world, but a new player is about to enter the game: AI agents that understand intent and execute actions without manual clicks.

The mission of AI is to do everything

For now, most AIs are confined to their own apps and forced to rely on middlemen to get anything done. That era is about to end.

For example, car owners typically have their onboard computer telling them when to make a turn to get to their destination. But autonomous cars are just around the corner, with a fully unleashed AI in direct control of the vehicle and the human driver having nothing to do except enjoy the ride. Some cars can in fact do this already, and a similar breakthrough is coming to your favorite digital device.

What if Gemini or ChatGPT could replace you as the user of your phone? Instead of manually opening your email app and typing a message to your boss, you could just tell your AI to write the entire email. The software, which you have permitted to access other parts of your device, could enter your mail folder, then compose and send the message without you having to do anything. Ask it to invoice your client, and it will generate the right Excel document in the blink of an eye.

Come to think of it, why should it need Excel at all — or any other app, for that matter, if the AI can do everything by itself? The output of a digital device is just pixels, sounds, and data, and AIs can already command those easily enough. Tell it you want to play chess, and it should be able to generate a chessboard without opening any kind of a specialized chess app. Extend this logic far enough, and the need for any app at all disappears.

The rise of the agent economy

OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta are developing multi-modal AI systems that can perform tasks across services autonomously. AI agents don’t just browse; they act — calling APIs, coordinating steps, and reporting results.

The more we rely on AI agents, the sooner we will experience an “interface collapse”, where users never see the apps that power their requests. This phenomenon is already apparent in the Meta Ray-Ban Display, a pair of smart glasses that has an impressive variety of functions but no traditional app store to support it.

Other companies are blazing a similar path. From OpenAI’s autonomous “assistant layer” to Twitter/X’s integration of AI directly into its user interface, the future of mobile interaction is no longer about opening apps — it’s about issuing commands. A bit further down the road, AI may just take over everything, making all other software obsolete.

This kind of future definitely has its appeal, turning your digital devices into a kind of full-time assistant who can do anything for you as soon as you ask. Our personal and professional lives will change radically alongside such a technology. But granting that much power to an algorithm requires a lot of trust, and it makes sense to wonder about the wisdom of putting software fully in the driver’s seat.

Privacy and independence in a world run by silicon

When one AI starts to manage your shopping, finances, and personal interactions, it becomes the most powerful intermediary in your life — raising the very same questions about monopoly control that we started with. Meta’s rollout of default in-chat AI assistants in Europe has already raised privacy and antitrust concerns, with regulators now questioning whether “default AI layers” amount to coercive design.

Data leaks are another concern. Sensitive information is vulnerable to theft under any arrangement, but entrusting it all to one algorithm would be the very definition of putting all of our eggs in one basket.

Apart from these pitfalls, there is also the question of accuracy. Today’s LLMs still hallucinate from time to time, but at least we humans have a chance of catching those mistakes before they pollute our information space. When AI agents start to perform tasks without our direct input, those hallucinations are much more likely to be sent out into the world where they can do real harm.

These challenges could play a big role in our relationship with technology over the next decade, and many of our brightest minds are hard at work trying to solve them.

For now, it’s worth remembering that the App Store isn’t dead — yet. But as AI agents become our new digital intermediaries, screens and icons may soon fade into the background, replaced by invisible layers of intelligence executing our intent.

These digital tools will certainly empower people to live more productively. But will we use that power wisely? And will we still be the authors of our lives, or will we all be at the mercy of algorithms that decide what we see and hear?